South Australian Medical Heritage Society Inc

Website for the Virtual Museum

Home

Coming meetings

Past meetings

About the Society

Main Galleries

Medicine

Surgery

Anaesthesia

X-rays

Hospitals,other organisations

Individuals of note

Small Galleries

Ethnic medicine

- Aboriginal

- Chinese

- Mediterran

The Port Adelaide Casualty Hospital 1862-1980

John Couper-Smartt

To understand the role played in Port Adelaide's life by its own " Casualty Hospital" it is first necessary to understand something of the history of Port Adelaide.

It was the task of Colonel William Light, as Surveyor- General for the proposed new province of South Australia, to determine the best site for both its capital township and its main harbour when the process of European settlement began in 1836.

J M Skipper sketched William Light on his death bed in October 1839.Original in La Trobe Library

It was he who decided that the harbour should be established in the upper waters of the (misnamed) Port Adelaide River but that the township should arise on the banks of the River Torrens some 12km away. This decision was questioned by many of the first settlers, including Governor Hindmarsh who had purchased land near Victor Harbor which he felt would be a better location. However, although already suffering from the tuberculosis that would soon kill him, William Light was able to achieve the establishment of both objectives.

The first landings of migrants and cargo took place in the upper reaches of the Port River, at a make-do landing stage amongst the mangroves at a site that later attracted the nickname of "Port Misery". It was meant to be a temporary arrangement although the poor financial state of the new province meant that it remained in use for nearly four years with vessels anchoring near the present site of Birkenhead Bridge and all cargo being hauled in punts and lighters across a couple of kilometres of shallow waters and smelly swamp. A winding bullock track ran from the landing place to the north western corner of Adelaide and hardly merited the grand title of " Port Road".

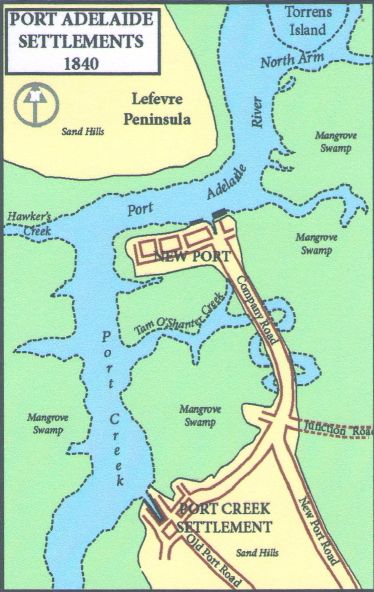

Aided by the vision of Governor Hindmarsh's replacement, George Gawler, a new port was eventually opened in October 1840. It was situated at the present site of Port Adelaide and was achieved as a result of a fascinating joint venture involving the colonial government and private enterprise in the form of the powerful South Australia Company. In a nutshell, the SA Company, under direction of its manager David McLaren, built a wharf and storehouse in return for an eventual gift of a prime section of waterfront real estate in the new settlement of "New Port" - or what is now Central Port Adelaide. More importantly, the SA Company constructed a new road, running through the mangrove swamp on a causeway, to join the existing Port Road at modern Alberton.

Port Adelaide map settlements 1840

This road provided a direct link over the 12 km between Port Adelaide and Adelaide. It was, of course, a very bumpy and often unreliable link. Transport was usually via bullock cart or the single horse "Port Cart" and, assuming the road was not flooded, would take several hours to cover the distance.

Port Adelaide was, therefore, a long way from Adelaide. It also soon saw itself as having very different requirements from Adelaide, in medical matters as much as anything else.

It should be remembered that whatever South Australia was short of in its early days it certainly was not short of medical practitioners. Although their medical training was very varied, all the migrant ships carried at least one doctor and/or surgeon to take care of the needs of their settler passengers. It should also be remembered that the popular medical view at that time considered a great deal of disease to be due to a combination of genetic deficiency and dissolute lifestyle. An important component of the South Australian colonial experiment was the theory that selecting honest, healthy and (preferably married) English labourers and tradesmen would lead to a society that was devoid of many of the social and medical problems that bedevilled life in industrial Britain. It was considered unlikely that such a colony would need a public hospital (ie one offering free treatment for indigent patients) and such organisations as a police force or a gaol were not included in the original plan.

Of course, all this was soon proven wrong.

Adelaide Hospital

Adelaide Hospital from a sketch drawn in 1860.(Reproduced in A History of the Royal Adelaide Hospital.)

Most will be familiar with Mr Estcourt Hughes' work published in 1967 (and helpfully revised in 1982) which covers the early years of that hospital very effectively. I will not expand unduly on the history of the Adelaide Hospital but it should be noted that the need for a "poor hospital" was apparent within a few months of colonisation and the Colonial Surgeon, Dr Thomas Young Cotter, established Adelaide's first hospital during 1837. Literally a mud but with a thatched roof, it stood somewhere on North Terrace in the vicinity of Trinity Church. Conditions in this "hospital" and its successors were abysmal without even the most basic of equipment or even any toilet facilities. Dr Cotter used his own money to attempt to improve the situation while embarking on a vigorous publicity campaign to increase public awareness of the situation. The government responded by setting up a Board of Management with the Colonial Chaplain as its chairman. Thomas Cotter disappears from view soon afterwards.

Much of the problem was that, however fit and eager they were when they set out, a gruelling sea voyage to a poverty-stricken colony with inflated commodity prices and scarce employment opportunities was sufficient to reduce many to a state of abject poverty and sickness.

Despite the obvious need, it was not until 1841 that Adelaide acquired its first purpose built hospital with 30 beds, built near the corner of North Terrace and Hackney Road. By 1850 this was already totally inadequate and in 1855 work had commenced on building a new hospital on the site now occupied by what would eventually become the Royal Adelaide Hospital.

Port Adelaide Casualty Hospital (1862)

Port Adelaide's first Casualty Hospital was one of the small buildings seen behind the police who had assembled for a drill in the 1870s. The rear of the Doctor's House is on the right with Government Building on the left.

In 1854, during this period when public concern about the overcrowding and poor conditions at the Adelaide Hospital was at its peak, a public meeting was held at the White Horse Cellars Hotel in Port Adelaide to push for a local hospital. By this time Port Adelaide had grown into a bustling settlement with a population of 500 people and a further 600 in nearby Alberton. Many hundreds of workers found employment in the factories, mills and smelters that clustered around the docks and a total of some 300 ships entered the port during that year. Port Adelaide had grown into a very busy town with many of its workers engaged in some very dangerous industries. Until the opening of the Port Adelaide-Adelaide railway line in 1856 it was a very long and painful trip for anyone with a serious injury to reach the overcrowded and debatable comfort of the Adelaide Hospital.

Port Adelaide was also a conspicuously unhealthy town. The site of the township had been a mangrove swamp until 1840 and a vigorous process of reclamation continued throughout the 19th century, using the silt dredged from the river during channel and wharf construction. In the 1850s the township remained prone to regular flooding with the much of its area below high tide level and protected from tidal inundation by mud embankments. Many houses stood well below the water level and their lower floors were permanently inundated. (As if this was not unhealthy enough, it was 1866 before the first mains water supply was installed — carrying water from Thorndon Park Reservoir along Port Road — and 1917 before central Port Adelaide was connected to a water-borne sewerage system. Adelaide had been the first Australian town to install its own sewerage system in 1881 yet many areas of Port Adelaide were still relying on "night carts" in the 1940s.)

But it was the frequency of industrial injury, and the vigorous support of the local trade union organisations, that drove the movement to open a hospital within Port Adelaide. This pressure was increased after Port Adelaide attained corporate status in 1855 and plans for a single-ward, purpose-built casualty hospital were drawn up in 1859. A site had been selected and hopes were high until the South Australian Government announced that it had withdrawn its support for the plan.

It is reasonable to assume that this was because the colonial government had already commenced work on the new Adelaide Hospital. The argument that Port Adelaide's sick and injured were well-served by the facilities in Adelaide ("less than one hour away") was to be a contentious point for decades. What was not helpful was the Colonial Surgeon's declaration that there were so few injuries in Port Adelaide that a hospital could not be justified. Just a short time afterwards a man fell overboard from a ship and died in Adelaide Hospital. A review of - the newspapers of the day shows that injuries were frequent and well-reported. Presumably any casualties that did arise were treated by one of the local doctors and only the most serious of cases would have been subjected to the painful journey into Adelaide

The first "Doctor's House on St Vincent Street in 1860. The Town Hall is to the left and the water police boat-house to the right. It was not as grand as it looked - the cellar was permanently water-logged and water rats chewed on anything that was not locked away.

The population of the Port Adelaide region had exceeded 4000 when continued public pressure finally gave the town its first hospital in 1861. Unfortunately it was nothing like the planned structure of two years earlier and was just a single room stone cottage behind the new police barracks and the grand new Government Building at the corner of St Vincent Street and Commercial Road.

Dr Handayside Duncan was Assistant Colonial Surgeon and local Health Officer with responsibility for Port Adelaide and was appointed as its first Medical Officer at a salary of £50 per year. He was assisted when necessary by a nurse employed on a casual basis.

A young Dr Duncan

A young Dr Duncan

It should be stressed that the government was adamant that the hospital was only to treat trauma cases. Dr Duncan was not supposed to admit anyone with an illness or an infective condition - they were to be sent to Adelaide by train. Similarly, since the hospital had only one room, no female patients were to be admitted. The fear on the first score was, in part, lest an infectious epidemic should be let loose in the adjacent police barracks. But the restriction on mixing male and female patients applied only while they were alive...

Under the Licensed Victuallers Act of 1837 all inn-keepers were required to retain on their premises any corpses brought to them that showed evidence of death from drowning or from trauma. This was partly because they usually had a cool beer cellar in which to store a body but also because hotels were then the usual venue for a coroner's inquest. Following an occurrence in late 1864 when the body of a seaman who had died after a fight was left in the tap room of the Port Hotel until the inquest was completed, the police adopted the custom of taking bodies to the new public hospital.

This led to a famous incident a few months later when a magistrate visiting the hospital found that the decomposing corpse of a woman was lying on the floor adjacent to a sick patient. The magistrate immediately directed that the body should be placed in a cell at the adjacent police station. The subsequent inter-departmental argument culminated in the construction of a "Dead House" (morgue) alongside the hospital in 1866 although, despite the vigorous protests of the Commissioner of Police and other occupants of the cells, an empty police cell been used as a makeshift morgue for several months. Twenty-five years later, after endless public protest, the morgue was relocated to the former gunpowder store on the outskirts of town on Frances Street.

Dr Handayside Duncan

Dr Duncan in his later years

There have been many interesting and even colourful medical practitioners in Port Adelaide but Dr Handayside Duncan merits particular comment. Born in Scotland in 1811, he achieved his Doctorate in Medicine at the University of Glasgow at the age of 21. After further study in Europe he settled in Bath where he married a colleague's daughter. He was 28 when the couple emigrated to South Australia, apparently following the conventional wisdom that the climate was beneficial to those prone to tuberculosis and similar lung diseases. Like most of his colleagues, he travelled out as a ship's surgeon/physician but he initially tried his hand at farming his own land near Marion before returning to medicine in 1841 in order to survive. The Adelaide Hospital had just opened at that time and, following the resignation of three of its honorary medical officers, he was accepted as an honorary physician and surgeon.

As noted earlier, there was an oversupply of doctors in Adelaide at that time and Dr Duncan's regular attempts to use his status as an "Honorary" to gain appointment to a government position came to naught although he was appointed as an unpaid member of the first Medical Board when it was established in 1844. Eventually he decided to settle in Port Adelaide as a general practitioner until, in 1849, he was finally able to obtain the position of Assistant Colonial Surgeon and Health Officer. Then, just as life must have seemed secure at last, his wife was killed in a riding accident in 1850.

As Health Officer Dr Duncan was responsible for both local community health and hygiene issues and also the assessment of all potential infectious hazards posed by ships arriving in the harbour from any overseas port. Following the arrival of smallpox aboard the Taymouth Castle in August 1855, the decision about whether to quarantine a vessel was taken out of the hands of the pilot officers and Dr Duncan developed a force of assistant health officers whose duty it was to board all vessels arriving from foreign ports and to report their findings to Dr Duncan. A couple of years earlier he had also taken on the duties of Immigration Agent, inspecting all new migrants and offering general assistance as well as medical attention.

The position of Immigration Officer was hard work but, from 1855, it brought with it a grand two- storied house on St Vincent street, immediately to the east of the Town Hall. The previous year Dr Duncan, then 43, married 19-year-old Anne Williams who bore him three children until dying of puerperal fever

soon after the third delivery. In 1867 he married again although his third wife, Emily Servante and her child were both lost during childbirth two years later. His daughter Annie Duncan acted as housekeeper throughout the remainder of his life and later wrote a fascinating account of Dr Duncan's life and times.

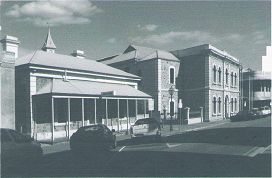

This view of Government Building in about 1880 shows the Doctor's House (left) alongside the Town Hall. Shortly afterwards it was demolished and replaced with a far grander building. Government Building was designed as a Police station (left), Court House (centre) and Custom-House (right) but was always too small to house all three organisations.

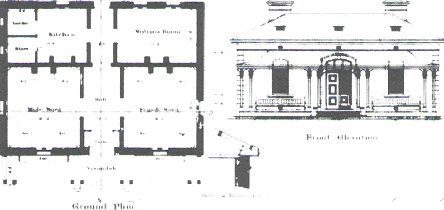

The architect's drawings for the new Casualty Hospital show the two ward layout with a central corridor and the kitchen and Matron's room at the back. Bench seats under the front verandah allowed patients to wait for treatment.

From 1862 Dr Duncan combined all of his various duties with that of Medical Officer of the Port Adelaide Casualty Hospital, yet still found time to run a private practice from his home on St Vincent Street and participate in many charitable endeavours. He basically worked until he died in 1878 when at his own request a post mortem was performed - allegedly to allay his own fears of premature burial.

During his later years Dr Duncan, after initially advocating the use of a hulk moored off Semaphore as a Quarantine Station, changed his views and played a key role in the establishment of the Quarantine Station that operated on Torrens Island from 1880 until 1971.

The Second Casualty Hospital (1884)

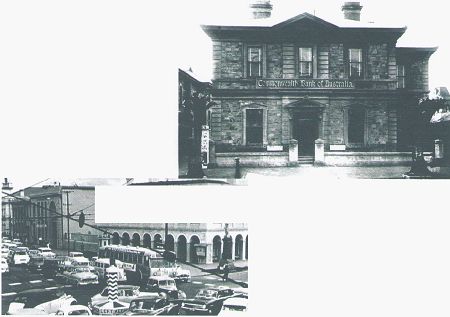

The second "Doctor's House", following its resumption by the Australian Government in 1915 for use as a branch of the new Commonwealth Bank

Lower photo: This view of "Black Diamond Corner" in 1965 shows, from the right, the Police station, the Post Office erected in 1928, the Commonwealth Bank with its 1930s frontage and the Town Hall.

The single-roomed hospital behind the police station was never adequate and, as the local population expanded, became increasingly unsuitable for use as a medical centre. There was growing pressure from local medical practitioners to construct either a medical centre with shared facilities or a local general hospital such as those opened in such townships as Mount Gambier. The colonial government would have none of this - arguing once more that Port Adelaide was adequately served by the Adelaide Hospital - but did suggest several surplus but totally unsuitable buildings that could be converted into a new casualty hospital.

Fortunately all of these proved unavailable or unsuitable and it was eventually agreed that a new building would be constructed. This was rather grander than the one-roomed shed and actually had a male and female ward, a kitchen and a room for a resident matron. (As recognition of the fact that nursing had now become a profession open to women. In the original hospital nursing duties were performed by a man who also assisted with maintenance, amputations and autopsies.)

Each well-lit and airy ward could accommodate four patients and, although hardly as large as the medical staff had hoped, was a great improvement on its predecessor. Matron was required to live on the premises and a night nurse was also employed.

One incident that tested the mettle of the Casualty Hospital occurred on 26 April 1924.

In No. 2 Dock SS City of Singapore, loaded with 38,000 cases of petrol, had been smouldering all day. The exhausted fire crews thought they had brought the fire under control when the ship was shattered by an enormous explosion. Three firemen died instantly and many of the wounded and burnt survivors were rushed to the Casualty Hospital for treatment.

The deaths are commemorated by a striking monument in Cheltenham Cemetery.

The Doctor's House

At the same time as the new hospital was erected, the house occupied by Dr Duncan's successor, Dr Robert Gething, was demolished and rebuilt as a 12-roomed mansion - although Dr Gething's sudden death meant that it was his brother-in-law and the hospital's third Medical Officer, Dr John Toll, who moved into the grand home.

Dr Toll departed to serve in the South African War in 1899, dying of infection while on the way home, and Dr William Gething became Medical Officer of the Casualty Hospital in his absence. He used the building as both a home and a clinic even after Federation transferred the duties of quarantine and public health services to the new Commonwealth Government. It came as a drastic shock to Port Adelaide when, in 1915, it was announced that the ailing Dr Gething and his public clinic would be evicted from the "Doctor's House" to allow its conversion into a branch of the Commonwealth Bank. Protest was ineffective and Dr Gething died soon afterwards. The house was drastically refurbished (destroying a wonderful wooden staircase in the process) but can still be seen behind the false front that was added by the bank in the 1930s.

A General Hospital for Port Adelaide

The new casualty hospital was kept in regular use. During its first year (1884) it had 88 "indoor patients" (ie those who required admission for at least one night) and about 50 who could sit on the benches outside while waiting for the doctor and then be discharged after treatment. Of those 138 patients the doctors treated 16 fractured legs, seven broken arms and 15 cases of concussion. Fifteen amputations were performed (despite the lack of any dedicated surgical theatre) and six deaths were reported.

This seems to have been the general pattern of life at the Port Adelaide Casualty Hospital over the next few decades. There was, of course, a steady increase in cases although there was little improvement in the clinical facility or the staff to deal with this. A nurse's room and a bathroom were added in 1909, enclosed within a verandah extension to the back of the building.

The figures for 1915 show that there had been little change in the number of in-patients over the years (74 males having been admitted of whom 8 had died) but the hospital had treated 1154 males and 75 females as out-patients. With the Great War entering its second year and the effects of the drought of 1913 still apparent, it is not surprising that Port Adelaide Council's push for an improved hospital fell upon very deaf governmental ears.

However, once the war was over, there was a steadily increasing wave of public and political pressure for a proper local general hospital to serve the region. In 1920 the Council even decided on its location, offering the government part of a block of land near the junction of Commercial and Grand Junction Roads (later the site of Port Adelaide Girls' High School). Over 61 the next thirty years there was to be an increasing and well-coordinated public clamour for a general hospital for Port Adelaide. This did not lose momentum even when Sir Thomas Playford's government declared in 1944 that the hospital would be built at Woodville.

It soon became apparent that the government had no intention of changing its mind about the site at Woodville but a new concern then arose when it was learnt that Wolverton Private Hospital (the only private maternity hospital in the area) was to close. This eventually resulted in the conversion of Wolverton into the Lefevre Community Hospital - the first such service in the metropolitan area - but the concern about the limited maternity services in the region meant that the first section of the new " Western District Hospital" to open in 1954 was the maternity unit..

The former Port Adelaide Casualty Hospital in Nile Street as seen in 2007.

Port Adelaide Special Clinic

The planning for Western District Hospital (soon renamed The Queen Elizabeth Hospital) had a profound effect upon the future of Port Adelaide Community Hospital. In 1943 it had already become the home of what was then called a "Special Clinic". These free clinics for the treatment of STDs were opened in all seaports under the terms of the Brussels Agreement of 1924. The work of the casualty hospital continued alongside the Special Clinic - although the two institutions were separate financial and employment entities. Strangely the Agreement allowed the supply of free treatment to men but not to women! The latter were supposed to be sent on to the "Night Clinic" at Adelaide Hospital. Many women were treated at Port Adelaide but it was not until 1968 that this treatment could be officially prescribed. At the same time the rather outdated facilities at Port Adelaide were substantially revised and a new clinic was eventually built behind the original Port Adelaide Casualty Hospital in 1979.

By this time it had become a very busy unit but times were changing. By 1981 the Port Adelaide Special Clinic had been absorbed within a new organisation, the Port Adelaide Community Health Service. In 1986 this entire service was relocated to its current site in Church Street. The old Casualty Hospital was taken over by Anglicare Inc. and serves as "Sobering-Up Unit". A small plaque recording that the building is "Dedicated to the pioneer doctors and nurses who served, and the pioneers that supported it" is the only obvious reminder of the building's great significance to Port Adelaide's medical heritage.

Sources and further reading

History of the Port Adelaide Casualty Hospital, Averil G Holt, Port Adelaide Community Health, 1991

A History of the Royal Adelaide Hospital, J Estcourt Hughes, Board of Management of the Royal Adelaide Hospital, 1967, Second Edition (Revised) 1982

Port Adelaide: Tales from a "Commodious Harbour", John Couper-Smartt & Christine Courtney, Friends of the South Australian Maritime Museum, 2003

-o0o-